Subash Kataria, grandson of Mukhi Takandas Kataria, pulls out a diamond from his treasure trove – a hand-written autobiography of his grand-father. The autobiography depicts the struggles that the great man went through in his early life. Subash, has outlined these in his forwarding notes.

Our Bhagnari community is no stranger to the plague. The community has suffered from the plague in the very early 1900s and many amongst us may have heard stories from our elders of those horror days.

Now a pandemic is visiting our world again.

In these days of Pandemic, let us all take inspiration from the true story of this young boy

• Who lost his father to the plague at 2 years of age.

• Lost his oldest brother to the plague too, then became an orphan at age 6

• Was rescued from drowning at age 2 and survived burns at age 7

• Got admission to school as a free poor student

• Was not allowed to sit for exams since fees were not paid

However, He was a bright young boy, full of determination, dedication and honesty. He had the zest to live and was not afraid of adverse and challenging circumstances.

He was a true visionary, much ahead of his time. He had faith in himself and his abilities.

He strived hard and lived with this simple motto: “ Satyamev Jayate” . Truth shall always prevail. He was a lad who grew up into a Man who believed in himself.

The fruits of his labour and his love for the Bhagnari community has touched and enhanced the lives of every one of us. This is the story of one of the greatest Bhagnaris ever born.

Let us today be inspired by this true story as written by him in his own hand maybe 60 years ago, and look at the present challenges of life and know that ‘THIS TOO SHALL PASS”.

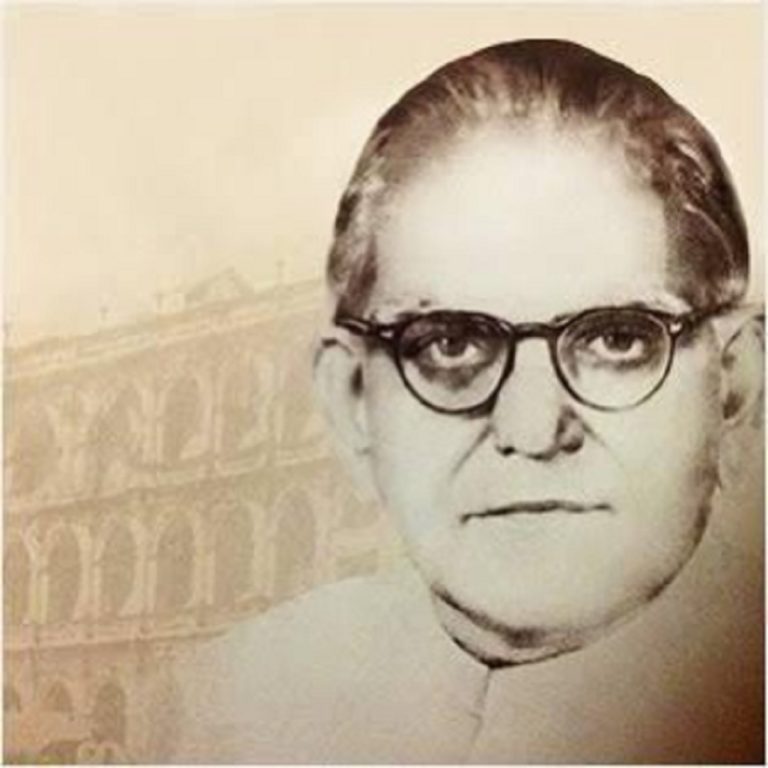

T. H. KATARIA

(TAKANDAS HEMRAJ KATARIA)

AN INCOMPLETE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

As written by his own hands

Date of Birth: 18-05-1898

Attained Immortality: 26-11-1966

(A listing as prepared by Shri Takandas Kataria himself:)

This autobiography is probably penned in the early 1960s

Elders (PRESIDENTS)

1 Harimal

2 Chainamal

3 Sharipal?

4 Shamdas

5 T.H.K.

OTHERS

(Can somebody please throw light on these names? I am not very familiar with these respected elders of those days)

Born in May 1898 at Karachi in Bhagnari Street previously called Pamoo dalal street, in a respectable family.

Ours was mercantile community and there were few English knowing persons in those days.

Shri Hemraj was a teacher in Govt. N. G. High School and the first matriculate in our Panchayat. Hemraj has an amicable nature so much so that some students over 20 years after death used to come and ask his sons as to how they were doing. Such sincerity could be expected only as a result of his very good treatment to his pupils.

When T. H. Kataria was a small infant his parents went to visit Sadhubella Sukkur and when

PAGE 2

boat was approaching Sadhubella Shri T H Kataria fell in waters, but he was saved by a boatman who jumped after him.

In 1897-1900 a very dangerous type of plague (called bubonic ) broke out. Every year in succession, whenever plague broke out people used to flee from Karachi with the sick here left unattended by their near and dear ones. There were few persons to attend on sick and Govt. used even their school staff

PAGE 3

to look after and attend the sick. It was contagious disease. Shri Hemraj was also kept on duty and he too got infected and died of the disease.

In the next 2 years, all the other earning members of the family also died and five sons of Hemraj, Beharilal, Lalchand, Kewalram, Parsram and Takandas were left with their mother without any earning member. There were 2 sisters fortunately already married. The boys were all young but Beharilal took the burden and

PAGE 4

( In plague days the authorities used to burn the belongings of the house to combat disease where a plague case was detected. Thus, all the belongings removable were destroyed. There will hardly be a family that’s not have been affected by plague at Karachi. )

PAGE 5

looked after the family though he was very young.

Unfortunately, he too died about 3 years later victim of same plague which used to invade Karachi every year. We were then living at Lehman Naka Camp about 4 miles away from town. Every year at the time of plague several camps were made in far off places and the residents used to go and live.

After Beharilal’s death it became a problem for the mother to feed her children.

PAGE 6

She had a well to do mother but no help came from that quarter and after couple of years of torture of poverty and difficulty of feeding the family she died of burns at Lady Dufferin Hospital. Her sons to her was a liability and not asset and she died looking after and worrying for them. The four boys became orphans. Takandas about 4-5 years, Parsram 6-7 years, Kewalram 8-9 years Lalchand 12-13 years ages. The society pressed on

PAGE 7

grand mother who was well placed and she took the 4 boys at her home. Thus the independent family came to a close and they lived with maternal grand mother.

She got 3 boys Lalchand, Kewalram and Parsram engaged as shop assistants in that young age on salaries of 15,7 and five per month. All effort was made to get Govt. help since Hemraj was a Govt. servant and died on Govt. duty. Rs. 10/- per month were sanctioned for the family until Lalchand became 18. Thus the earning of the family became 37 a month which in those

PAGE 8

days could sustain a family of that size. Which was about 4/- a month;

Ghee about 40-50 a maund, milk for 0/1/6/ for pau seer. You can buy in the market vegetables etc. for pies also.

Things went on for some time , salaries gradually increased, the youngest Takandas was sent to Sanatan Dharam School where he was admitted as a free poor student though the fees were only 0/2/5 per month.

PAGE 9

At the age of about 6-7 years Takandas got seriously burnt in Diwali by crackers but he survived and this was second escape from death.

He was bright student and used to get good rank.

When Lalchand was about 18 , in grandmother’s family there was only one son who had three daughters. He was betrothed and after a year got married. He had been accepted as one of the best salesman and was drawing a salary of 60/- which was then in those days a good salary. Kewalram 40/- and Parsram 30/-,

PAGE 10

after some time the 4 brothers left the grandmother’s house and rented a house and lived separately. Grandmother asked for about 400/- which she had spent on marriage which were paid to her by instalments. Lalchand had a weakness of living luxurious life. The family therefore had always financial difficulty though earnings were more than ordinary requirements.

After couple of years Lalchand’s wife died and there was no lady left in the family.

PAGE 11

They brought the aunt who looked after the house. Kewalram also had grown up and both got married. Loans were taken from their Seths which were paid by instalments.

We moved to bigger rented house since 2 were married. As there were differences between the aunt, and Shri Lalchand and Kewalram , aunt left for her mother’s house.

Lalchand started managing the affairs but his weakness for luxury left the family always in financial difficulties.

PAGE 12

At this stage our brother in law Bojraj suggested that he would like us to become partners in a caps shop which he intended to open and wanted Parsram to manage. Shri Parsram was a very good salesman. Shop opened and he was in charge. Business was alright and paying but Shri Bojraj had some financial burden. Parsram got married to the daughter of a respectable man Shri Lilaram of Hyderabad and we all had to go there…

PAGE 13

Shri Bojraj had to close his business and we were advised also to close business as Bojraj was partner who had financed the show. Thus this business, where even our share of profits was invested was lost and nothing received.

Parsram then got an offer from one Kalyandas who had a shop in the Law Bazaar to join him as working partner. He along with his friend one Jethanand Murjimal Who promised to finance the business and the firm of 3 partners started.

Kewalram had also been getting a good salary and so was

PAGE 14

Lalchand. Takandas was a student and he had joined English school and the fees in those days were 1/4/- a month. This too was difficult to pay. For not paying fees he was not allowed to sit in the exam of the first std. and lost a year. He felt very much and joined the school a fresh. He got a promotion after 6 months as he was a bright boy. The school was middle school and there were only 5 students. He studied

PAGE 15

Up to 5th standard there and remained monitor in 2-3-4 and 5th standards. After passing 5th he tried to get entry into High School but failed so he joined C. N. S. High School. As he was bright boy he got the top rank there too and was liked by the Head master and Principal.

As the family had again got into financial difficulties due to certain weaknesses of Shri Lalchand it became necessary to leave studies.

The Headmaster and Principal offered financial help as they wanted a bright boy

PAGE 16

to continue but Takandas refused.

Mrs. Beharilal’s mother in law then brought in Mrs. Beharilal and requested us to keep her in the family and took the burden which was morally ours. We agreed and she lived with us. This was about 1912. He tried to get job but it was very difficult.

He got a temporary clerical job

PAGE 17

In an European firm at Kiamari

He was not liked by two staff as he was quick to finish the work which was mostly calculations whereas they wanted him to go slow.

This job also was over after 2 months.

After trying for 6 months he arranged for a job for Singapore but was not allowed by the family. He then got a loan of 100/- from Shri Bojraj and joined as a partner one Katumal Auctioneer but nothing came out of that auction business as Katumal was happy go lucky man who would spend away the sales with the result 100/- more lost and he had to hunt for jobs. Having married, for a year more he got no job. Lalchand was serving, Parsram was on partnership business, Kevalram was serving one Shri Thariamal Khemchand.

Kewalram persuaded Shri Thariamal to keep me as shop assistant to see if I could be useful.

I joined Seth Thariamal.

He had a Gujrati in his staff.

PAGE 18

Who was a salesman as well as a Gujrati correspondent as letters to Bombay used to be in Gujrati.

The Gujrati assistant did not turn up on duty next day as he thought I may later replace him.

Later Thariamal felt he had lost a man because of me and he tried to look for a man but to his pleasant surprise he found his sales having increased by 50% within 10 days though I was new.

The business was general merchant which consisted Hosiery, cutlery, fancy goods etc.

(…… This is the last entry of the available pages……. )

A note: The currency in those days were Rupees/Anna/Pies

An anna (or ānna) was a currency unit formerly used in british India and Pakistan, equal to 1⁄16of a rupee. It was subdivided into four (old) Paisa or twelve pies (thus there were 192 pies in a rupee). When the rupee was decimalised and subdivided into 100 (new) paise, one anna was therefore equivalent to 6.25 paise.

THANKS are due to Shri Ramesh Poplay who helped me transcribe some of the words in the hand wrtiiten document as well as to my mother in law Smt. Lata Ramchand Gangaramani who helped me to understand the events as well as the currency of those days. Thanks also to Shri Gobind Mehta and to Shri Lalit Jham for their valuable inputs.

Just a few of the numerous milestones in the life of Shri Takandas Hemraj Kataria:

• . The establishment of Kataria Optical Factory, India’s very own and first factory to produce spectacle frames.

• The establishment of the chain of optical stores under the banner of Takandas H Kataria

• The making of Kataria Nivas and Kataria Colony

o The longest serving Mukhi of Shree Bhagnari Panchayat

o The President of the All India Sindhi Panchayat Federation

o The Uncrowned KING of the Optical Industry in India in his days

o Being conferred with the title of SIND KESARI by the Federation

Memory of Shri Takandas H Kataria is perpetuated by

The Kataria Colony which is today an internationally known landmark

The Takandas H Kataria Marg , both in Mahim – Matunga in Mumbai as also in Ulhasnagar

The Library run by Kalpana Friends Circle in Ulhasnagar

ON MAY 18, 2020, IT WILL BE 122 YEARS SINCE SHRI TAKANDAS H KATARIA WAS BORN.

NEARLY ALL THE PEOPLE WHO CAME INTO HIS CIRCLE, BE IT OUR COMMUNITY , THE OPTICAL INDUSTRY, THE SINDHI PANCHAYAT OR IN POLITICS, PROSPERED IN LIFE.

Click on the following link to view the autobiography is Mukhi Takandas Kataria’s own handwriting:

https://ebhagnaris.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/THK-Daddys-partial-autobiography-29-Apr-2020-6-45-pm-1.pdf